Health

Do Children with Cats Have More Mental Health Problems?

Researchers explain why there are so few studies of human-cat relationships.

Posted March 22, 2018

Cats don’t get much respect—at least among researchers who study the relationships between pets and people. For example, at the 2017 conference of the International Society of Anthrozoology, 32 presentations reported results of studies on the bond between humans and dogs, while only four were devoted to cats. This neglect of our feline companions is puzzling. After all, more cats than dogs live in American homes.

The dog/cat mismatch is particularly pronounced when it comes to research on the links between pet ownership and health. Hundreds of studies have examined the impact of dogs on the health and happiness of their owners. In contrast, only a handful of researchers have investigated links between owning a cat and human well-being. Further, the results of these studies have been decidedly mixed. For example, Dutch researchers found that elderly cat owners were more likely to use mental health services and less likely to get regular exercise than elderly people without pets. And while this study found that cat owners were less likely to die from cardiovascular disease, another study reported that cat owners with heart conditions had higher death and hospital readmission rates than non-cat owners. And this study found that cat-owning women were more likely to be heavy drinkers than non-cat owners. Finally, this 2018 study of older adults reported that living with a cat was associated with more chronic illnesses and less successful aging.

Pets and the Mental Health of Children

The question of whether dogs and cats are good for kids is particularly important. Investigators from the Bassett Research Institute recently compared the mental health of 370 6- and 7-year-old children who had dogs with 273 children who did not live with a dog. They found that kids with and without dogs did not differ in their levels of physical activity, BMI, or history of mental illness. In one area, however, children with dogs were better off: They were less anxious. While 21 percent of children without a dog suffered from clinical levels of anxiety, only 12 percent of children with dogs did. Parents of kids with no dogs were particularly likely to report that their kids were afraid to go to school and to describe their child as shy.

Their study was published by the Center for Disease Control and was instantly picked up by the national press. As is often the case with studies of the impact of pets on human health, most of the media got it wrong. For example, the researchers repeatedly emphasized in their journal article that their results did not show that having a dog caused kids to be less anxious. Indeed, they wrote, “No cause and effect can be inferred. This study does not answer whether pet dogs have direct effects on children’s mental health or whether other factors associated with the acquisition of a pet dog benefit their mental health.” But, in their quest for upbeat stories, the press ignored the researchers’ admonition that their results should not be used to promote pet ownership. Indeed, the media charged boldly ahead with headlines such as “Here’s a Reason to Get a Puppy: Kids With Pets Have Less Anxiety!"

What About Cats?

When I read the Bassett Institute dog study, I was impressed with the results. But I also wondered if kids with cats would also be less anxious. Fortunately, we now have an answer to this question. Led by Dr. Moira Riley, the researchers recently revisited their data. This time they compared the 180 children who lived with cats with the 463 children who did not have cats. The results will appear in a forthcoming issue of the Human-Animal Interactions Bulletin. Cat owners, however, may not be happy with the findings.

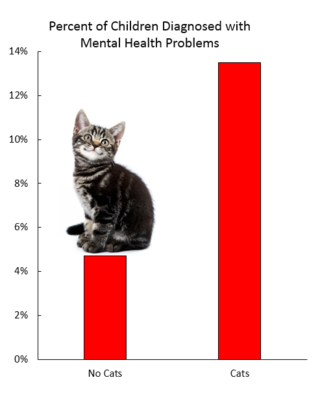

Based on their dog results, the researchers hypothesized that kids with cats would have fewer mental health problems than children without cats. They were wrong.

- Children with cats were nearly three times more likely than children without cats to have been diagnosed with a mental health problem.

- Cat-owning kids had significantly more attention problems, even after the researchers statistically controlled for factors like poverty, age, and parental depression.

- Finally, unlike with dogs, there was no evidence that having a cat was associated with lower rates of anxiety.

But why should living with cats be linked to mental health problems in young children? I can think of several reasons.

First, it is possible that something about cats produces more psychological issues in kids. It is, however, unclear what the mechanism of such an effect could be. The Bassett Institute researchers raise the intriguing possibility that the attention problems in children with cats could be caused by Toxoplasmosis gondii, a tiny parasitic organism that can invade the cells of mammals, including cats and humans. Some studies have reported that Tox infection is a risk factor for mental health problems, including attention disorders. However, these results are controversial, and other researchers have not found associations between Tox and human psychiatric problems.

Second, factors unrelated to cats per se could be at the root of the problem. For example, a recent study in the journal Anthrozoos reported that compared to dog owners, cat-owning adults scored lower on measures of positive emotions and conscientiousness and higher on scales measuring negative emotions and neuroticism. Though I think it is highly unlikely, it is theoretically possible that the types of adults who choose to live with cats are also more likely to have kids with psychological issues. That is, the causal arrow could conceivably point the other direction. As a cat owner, I don’t particularly like this idea.

Finally, the findings could be simply a statistical fluke. In any research involving samples of people, it is possible that some of the "statistically significant" results are due to random chance. This is particularly true of studies with multiple outcomes measures.

Why So Few Cat Studies?

Clearly, more research on the bond between humans and pet cats is needed. This raises the question: Why are there vastly more studies of the impact of dogs on human health and well-being than there are cat studies? To answer this question, I turned to three experts. Psychology Today blogger John Bradshaw is a pioneer in the study of human-animal interactions and the author of the books Cat Sense and The Animals Among Us. Carri Westgarth studies the impact of pets on human health at the University of Liverpool, and Mikel Delgado is an applied cat behaviorist and researcher at the University of California, Davis School of Veterinary Medicine. Here are the responses they gave when I asked them why there are 10 times more dog papers than cat papers presented at our research conferences.

Carri Westgarth: "Money. I think the health implications of dog ownership have been a more obvious place for funders to start because of the logical physical activity hypothesis. Now that we have a better understanding of what dog owners are telling us about how owning a pet impacts their mental health as much as physical health, then the door is open to try to get funding to look at cat ownership."

Mikel Delgado: "I can think of a few potential reasons off the top of my head why there is so much more research on dogs than cats....

Funding: I'm guessing a lot of the dog research is related to some form of animal therapy, or research regarding the effects of companion animals on children with autism, or aspects of pet ownership that might be related to health (increased exercise, etc.). I would guess that the National Institutes of Health and related funding sources are more likely to fund research with dogs. And because of the lack of cats who are well socialized for work as "therapy animals," it's much easier to do that sort of research with dogs. So people interested in cats probably aren't applying for that money in the first place!

People's attitudes about cats: Cats are still frequently perceived as "anti-social," "solitary," "aloof," etc. So it may not even occur to some researchers that there's much of a relationship between cats and humans worth studying.

The lack of human-animal interaction researchers studying cats limits the number of students studying cats."

John Bradshaw: "Raising funds for dog-related research is easier, (a) because dogs are widely used by agencies involved in therapy, detection, protection etc. and (b) because of the social issue of "dangerous" dogs and canine aggression in general, so there is political momentum." I also think that there's an underlying biological reason. Dogs make their primary attachments to people, so they are (a) easier to study in controlled settings when examining their cognitive abilities, (b) better suited to being moved from one therapeutic setting to another — hence more diversity of therapeutic uses, hence more research. Cats, as territorial animals, make their primary attachments to specific locations, hence can behave abnormally when in unfamiliar places. Most only behave normally in the rather uncontrolled surroundings of their owners' homes, so are much less suitable than dogs for studies of cognition, etc."

I agree with my three anthrozoological colleagues. Our field's surprising lack of attention to the human-cat relationship represents a confluence of money, species differences, and the interests of individual researchers. But, whatever the reason. Dr. Riley and her colleagues were correct when they wrote, “In conclusion, the risks and benefits of household cat ownership are not well understood.”

LinkedIn Image Credit: AlohaHawaii/Shutterstock

References

Riley, M. R., Gibb, B., & Gadmski, A. (in press). Household cats and children's mental health. Human-Animal Interaction Bulletin.